Naomi Salmon, Department of Law and Criminology, Aberystwyth University, Wales, UK

Following hot on the heels of the ‘Biotechnology Revolution’, the ‘Nanotechnology Revolution’ is now gathering steam. After twenty or so years of basic and applied research, industry players are now seeing the fruits of their R&D investments incorporated into all manner of products ranging from high performance tennis rackets and anti-odour socks to self-cleaning glass, food packaging materials and sunscreen lotions1.

According the US based Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies2 upwards of 800 manufacturer-identified nanotechnology-based consumer products are now available on the global market3, with new products being launched at the astonishing rate of three to four per week4. Global trade in Nanoscience and Nanotechnologies (N&N)-based materials, products and services has grown exponentially over the last four or five years – by hundreds of billions of euros, in fact – and it is now widely predicted that the nanotech sector will be worth somewhere in the region of 1,000 billion euros by 20155. There may not be any nanofoods, as such, available in EU supermarkets at present6, but with numerous innovative food and food related applications in the pipeline (including smart packaging, on demand preservatives and interactive foods)7 the nanofood sector alone may well be worth as much as 20.4 billion USD by 20108.

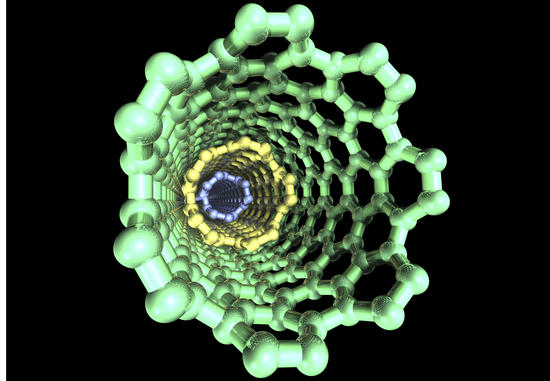

Before proceeding any further it is useful to provide some clarification of key terms. The prefix ‘nano’ originates from the Greek word for ‘dwarf’, and in science and technology it is simply used to denote scale: one nanometre equates to one billionth of a metre (i.e. 109 metres). The reality of materials at the nano-scale can, perhaps, be best visualised using familiar materials as a reference point. For example, a chain of five to ten atoms measures approximately 1nm and a single human hair has a diameter of around 80,000nm9. This seems straight forward enough. However, it is important to note that despite a growing consensus that, for regulatory purposes, the ‘nano’ pre-fix should be applied to designed and manufactured particles having dimensions less than 100 nanometers (< 0.0000001 nm)10 there is not, as yet, any universally agreed formal threshold below which a particle will automatically be designated a ‘nanoparticle’.

‘Nanotechnology’ as a broad umbrella term can be fairly easily defined. In the words of the European Commission:

“Conceptually, nanotechnology refers to science and technology at the nano-scale of atoms and molecules, and to the scientific principles and new properties that can be understood and mastered when operating in this domain. Such properties can then be observed and exploited at the micro- or macro-scale, for example, for the development of materials and devices with novel functions and performance.”11

This being the case, it should come as no surprise to find that the EU has high hopes for nanotechnologies. The expectation is that this latest generation of new technologies will offer wide-ranging economic, consumer and environmental benefits12. However, whilst both national governments and the EU institutions are certainly keen to present a rosy view of the nanotech landscape, ongoing uncertainties ensure that they must, at the same time, acknowledge the euphemistically labelled “knowledge gaps” that currently frustrate efforts to assess and fully evaluate the potential risks associated with manufactured (or engineered) nanomaterials – particularly ‘free’ engineered nanoparticles13. As the Commission commented in its 2007 Action Plan for Europe,

“[w]hile N&N offer a number of beneficial applications, the potential impact on the environment and human health of certain nanomaterials and nanoproducts is not yet fully understood.”14

The UK’s (less economically minded) Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution has been rather more forceful in its assessment of the status quo. In its recently published report, Novel Materials in the Environment: The Case of Nanotechnology,15 this respected body of experts concluded that:

“Currently it is extremely difficult to evaluate how safe or how dangerous nanomaterials are because of our complete ignorance about so many aspects of their fate and toxicology.”16

Such admissions have a somewhat familiar ring to them, for they are highly reminiscent of those issued in relation to the creations of the burgeoning life sciences industry in the 1990s. Moreover, the regulatory challenges associated with emergent nanotechnologies – generated and compounded by conflicting policy objectives, and the mismatch between commercial realities and the current state of scientific knowledge – are also rather familiar. Numerous official statements emanating from the EU institutions refer to the obligatory “high level of protection” of environmental and human health safety demanded by the EC Treaty17 and the need to pursue “a proactive approach”18 to risk analysis and regulation.

There are, however, two important points to note here. First, “level of protection” mandated by the Treaty has a rather specific context: after all, this agreement both provides the foundation for, and (by virtue of the amending treaties) is the product of, a European project primarily directed at promoting and facilitating free trade within and between Member States. In fact, it was not until thirty years after the Treaty of Rome was signed that consumer protection was finally dragged onto centre stage as a mainstream policy objective at the Community level19. Prior to the 1990s, such matters were largely treated as peripheral, with the consumer protective value of supra-national legislation being essentially a by-product of the broader market harmonization programme rather than a direct consequence of any overtly consumer-centric agenda.20 Today, though the stakeholder sitting at the end of the supply chain certainly enjoys a higher profile than in the past, there is no constitutional obligation to ensure that the consumer benefits from the highest level of protection possible in any particular context. Instead, Treaty references to a “high level” protection must be understood as simply requiring regulators to provide consumers with adequate protection, i.e. a level of protection that is high enough, bearing in mind the potential for conflict between the interests of the consumer and those of other key players in the market.21

Second, returning to the matter in hand – the Nanotech Revolution – once the carefully polished veneer of Community rhetoric is scraped away it becomes clear that, just as was witnessed in the early years of the Biotech Revolution of the 1990s, policy-makers are, yet again, engaged in a rather uncomfortable game of regulatory catch-up. Notwithstanding repeated assertions that the EU’s stance on nanotech policy is proactive, and that the interests of both consumer and environment are being prioritised, the evidence tells a rather different and somewhat worrying story.

The uncomfortable truth is that within the market-oriented EU system there are various factors at play that, together, serve to ensure that any attempt to adopt a generalised and overtly proactive regulatory stance on nanotech is not only highly problematic on a practical level, but also untenable under Community law. First, on a practical level, commercial realities have already outpaced the law: the unprecedented rate at which nanotechnology is now infiltrating all market sectors has already rendered the adoption of any considered and generalised EU-wide programme of proactive regulatory interventions an impossibility.

Beyond the practical difficulties that arise when regulators seek to shut the stable door after the horse (or at least, some of the horses) have bolted, there are other, more fundamental barriers that limit the scope for effective management of ‘nano-risks’. These concern the troubling tensions that must inevitably arise wherever the hegemony of free trade (faithfully supported by the EU system) finds itself challenged by the ‘manufactured’ or ‘technological risks’ that tend to accompany emergent new technologies22. The bottom line is that as a system rooted in, and policed by, the rules of ‘The Market’, EU governance systems cannot easily negotiate, or accommodate, uncertainty within risk management systems.

As per the founding treaties, and as is the case in respect of other more familiar and less contentious categories of products, EU trade in nanotech products is underpinned by a strong presumption in favour of free trade.23 The starting point is always that barriers that hinder (whether by accident or design) the free movement of goods around the Internal Market are inherently bad. This being the case, the scope for States to restrict or prohibit trade in any specific class of goods within their own territory – even on safety grounds – is limited, with unilateral recourse to safeguard measures being rigorously policed by the European Commission and, ultimately, the European Court of Justice.

The key benchmarks against which the legitimacy and, thus, the lawfulness of any trade restrictions imposed upon goods moving within or between Member State markets are measured are the objectively quantifiable benchmarks of economic costs and science-led risk assessment. The clear advantage of this approach, from the free-trade perspective at least, is that it leaves little room for discretionary regulation informed by other, more subjective, factors or considerations – such as consumer opinion or preferences, for example. In other words, these benchmarks minimise the scope for States to act in a protectionist manner. In the general fray of the marketplace populated by familiar products and familiar (measurable) risks this approach may prove adequate.24 But what happens when science simply cannot provide the necessary benchmark against which to measure material risks to human health or the environment? Or, indeed, when science cannot provide the baseline from which the economic costs attached to the realisation of uncertain technological risks might be extrapolated with any real degree of confidence? Thus, despite the obvious problems inherent in such an approach (not least, from the consumer perspective), the presumption in favour of the free movement of goods that underpins the EU project is not automatically or wholly displaced by uncertainty.

Moving on, it is interesting to consider in a little more detail just how EU law is shaping up to the (uncertain) challenges now facing it as the Nanotech Revolution gathers steam. So, whilst the general population remain largely unaware of the growing impact of nanotechnology on their daily existence,25 the europa website26 reveals that the last five years or so have borne witness to a veritable flurry of activity as EU institutions have scrambled to pre-empt any possibility of a politically and economically costly consumer backlash against this latest generation of new technologies. In the words of the Commission:

“Europe must avoid a repeat of the European ‘paradox’ witnessed for other technologies and transform its world-class R&D in N&N into useful wealth-generating products in line with the actions for growth and jobs, as outlined in the ‘Lisbon Strategy’ of the Union.”27

Numerous publications emanating from EU institutions have sought to address the taxing question of how to nurture (profitable) innovation whilst also negotiating (potentially costly) uncertain risks make very interesting reading.28 For current purposes a brief comment upon two fairly recent offerings from the European Commission should prove adequate to illustrate the broad character of EU N&N policy and governance and, in particular, the official stance on risk management in the particular context of ‘nano-risks.’

The first of these publications is the European Commission’s Code of Conduct for responsible nanosciences and nanotechnologies research,29 adopted early in 2008. The Commission’s aims here appear to be twofold. First, this guidance document has clearly been drafted with a view to promoting EU-wide adherence to a uniformly responsible and open approach to the development of nanoscience and nanotechnologies. In essence, the Code seeks to provide a general statement on what should be considered to constitute ‘good practice’ in the emergent field of N&N – for the benefit of all concerned parties. Second, it is, no doubt, hoped that the timely publication of such a statement, will successfully forestall a troublesome consumer backlash. Thus, a reading of the text conveys a sense that the Code not only prescribes a (pre)cautious development of this sector, but also (reassuringly) that its provisions reflect current political and industry practice.

Of course, whilst the Code may reflect current practice across EU Member States, in so far as it is intended to dictate practice, its influence is somewhat limited: as a soft law measure, its provisions do not have any legally binding authority. Moreover, so far as the all important question of precaution is concerned, the Code does no more than tow the ‘Party line’. Though reassuring in its tone, the various references to precaution and the precautionary principle found in the body of the Code go no further than acknowledging the general (qualified) obligations set down in Article 174 of the EC Treaty30 that have since been elaborated in the Commission’s Communication on the Precautionary Principle:31 i.e. ‘economic precaution’ – the ‘safe’ and uncontroversial formulation of the principle that retains sound science and (economic) cost/risk/benefit assessments as its core components.32 There is certainly no attempt here to accommodate a less economically bounded version of the principle – more akin to that supported by consumer and environmental NGOs33 – that might stifle innovation and compromise Member States’ economic ambitions.

The other European Commission publication of particular interest here is a Communication (also published in 2008) entitled Regulatory Aspects of Nanomaterials.34 Here, the Commission attempts to present an open and calmly reassuring account of how the Union’s pragmatic (industry friendly) approach to the regulation of this new generation of engineered substances and products will work in practice. The basic message here is that “the Community legislative framework generally covers nanomaterials” and that it is the practicalities of implementation – specifically test methods and assessment methods – that need “further elaboration.”35 In other words, contrary to the claims of NGOs such as Friends of the Earth, nanomaterials are not entering the supply chain in some sort of ‘regulatory void.’36 The root of the problem, according to the Commission, lies in the fact that “the scientific basis to fully understand all properties and risks of nanomaterials is not sufficiently available at this point in time.”37 In essence, knowledge gaps render the application of the regulatory risk analysis – that informs both pre-market authorisation procedures and post-market monitoring requirements – less than straight forward.

Predictably, in its the opening paragraph, the Commission immediately reiterates the EU’s general commitment to a “safe, integrated and responsible approach” to the supervision of the emergent nanotech sector; an approach that is now, incidentally, regularly described as sitting at the very “core” of the Union’s policy in this area.38 Once the preliminaries have been dispensed with, the Commission moves on to more difficult (and hazardous) territory: a review of the rather pot-holed regulatory landscape. Thus, the main body of the Communication attempts to explain just how, and to what extent, existing regulatory controls are capable of ensuring a (relatively) safe and profitable development of the European nanotech industry in the face of significant challenges – the most notable (according to the Commission, at least) being the urgent need for a “rapid improvement of the scientific knowledge basis to support the regulatory framework.”39

It is interesting to see how the ambitions of profit maximisation and responsible governance (which, in themselves, provide plenty of scope for tension and conflict) are reconciled with the admission that the knowledge base upon which such governance must be based is currently somewhat less than adequate. The Communication reviews various key areas or aspects of regulatory oversight under a number of general headings (Chemicals; Worker Protection; Products; and Environmental Protection), but for our purposes, a brief discussion of one of these areas these will be sufficient to demonstrate the Community’s general approach to the opportunities and risks on the Nanotech horizon.

So, let us take the first of the Commission’s headings: Chemicals. The core legislation governing the manufacture, placing on the market and use of chemical substances is now Regulation 1907/2006 concerning the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals (REACH).40 The basic premise of the (recently revamped) European chemicals regime is that manufacturers, importers and, also, downstream users must ensure that substances produced, marketed or used by them “do not adversely affect human health or the environment.”41 Moreover, Article 1(3) expressly restates (and reinforces) the broad Treaty requirement that such a regime should be underpinned by the precautionary principle – albeit, of course, economic precaution.42

Importantly, from the perspective of regulatory coverage, although the Regulation does not expressly bring ENMs within its scope, it is now generally accepted that such substances are at least capable of being be caught by the “substance” definition set down in Article 3(1) of REACH:

“substance: means a chemical element and its compounds in the natural state or obtained by any manufacturing process, including any additive necessary to preserve its stability and any impurity deriving from the process used, but excluding any solvent which may be separated without affecting the stability of the substance or changing its composition.“43

Similar assumptions have been made as regards the coverage of various other sector and product specific legislation: hence, the Commission’s optimistic assertion regarding the starting point for nano-governance.44 However, whilst there is scope for nanomaterials to be captured by the REACH regime, it is important to flag up the short-comings of this legislation vis-à-vis nanoform substances. The fundamental problem here, is that neither REACH, nor indeed, any of the (product or sector specific) regulatory frameworks currently in force that must, for the time being at least, be relied upon to protect consumer and environment from ‘nano-risks’, have been drafted with the governance of a nanotech industry in mind.

This can be seen in that the primary target of REACH is chemical substances in their traditional bulk form and this both informs and defines the substantive content of the law. This is reflected in the quantitative regulatory triggers built in to the framework: the basic requirement that manufacturers and importers of chemicals submit a registration dossier to EU authorities only comes into play where chemicals are manufactured or imported in quantities of 1 tonne or more per year, and the full force of the comprehensive assessment and registration procedures do not kick in until the threshold of 10 tonnes per year is met.45 It seems obvious that chemical substances in nanoform are unlikely, as a matter of course, to be produced or imported in quantities large enough to automatically trigger the primary assessment and monitoring mechanisms provided for in this Regulation.

So, how has the Commission arrived at its conclusion that these unconventional chemical substances can be captured by REACH? As is commonly the case with Community measures, and in keeping with the (economic) precautionary credentials of the EU, some additional ‘safety-net’ provision has been incorporated into this regime. Thus, where a chemical substance raises particular safety concerns, the European Chemicals Agency is empowered to demand that the manufacturer or importer provide whatever information the Agency deems relevant and necessary – regardless of the standard minimum requirements of the Regulation.46 Moreover, when a chemical substance marketed in its bulk form is subsequently marketed in nanoform, the registrant will be obliged to update its registration dossier to ensure inclusion of information relating to classification, labelling and additional risk management measures. Any relevant risks management measures and nano-specific operational conditions will then (assures the Commission) have to be communicated down through the supply chain.47

The obvious problem here, of course – aside from fact that registration and licensing systems have proven to be less than wholly effective in the past48 – is that where uncertainty (or even ignorance) prevails, identifying particular safety concerns and then extrapolating specific information needs from those concerns may prove to be something of a game of chance; particularly where the quantities of nanomaterials are small and the industry players concerned feel disinclined to draw (unnecessary) official attention to their product.

The ultimate fall-back position is, so far as environmental and human health protection are concerned, the safeguard clauses of the Regulation that allows Member States and the Commission (in its role as EU risk manager) to impose restrictions upon the manufacture, use and/or placing on the market of nanomaterials deemed to present an unacceptable risk.49 As always, trade-restrictive protective measures are to be viewed as “provisional” in nature and, in order to be lawful, must be supported by an adequate evidence base – albeit a somewhat less than comprehensive dossier of scientific evidence where so called “knowledge gaps” render a full blown scientific assessment of risk impossible.50 On top of all this, the potency of the safeguard clause is further undermined by the Commission’s determination here, as elsewhere, to view economic viability a mandatory reference point for (legitimate) recourse to precaution.51

No doubt, some hazardous nanomaterials will be caught by the regulatory safety nets provided in REACH. And, no doubt, some hazardous nanomaterials will be caught by the primary or fall-back safety provisions of other key sectoral and product specific legislation. However, from the consumer perspective, the current state of play is far from satisfactory. The bottom line is that at present any coverage of nanomaterials is incidental rather than deliberate. Worryingly, the poor ‘fit’ of existing regulatory frameworks (such as the quantitative ‘triggers’ built into REACH) render it likely that, in some cases at least, identifiable safety concerns may well fail to emerge until after an engineered (nano)substance has entered the EU market. It is also worth remembering that even where novel substances are the subject of ostensibly rigorous targeted regulatory controls – as has been the case with genetically modified organisms since the 1990s – ‘accidental’ releases of GMOs into the environment and wide-spread contamination of the food chain have, nonetheless, occurred.52

Whilst industry may not be too concerned about such possibilities, consumers may well wonder whether they are being sold a little short – both in terms of safety and choice. As regards the latter issue, it should be noted that the EU’s regulatory pragmatism extends also to issues of labelling: there are no plans to introduce mandatory labelling of ENMs.53 Significantly, in its recent report, the UK’s Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution concluded that there is certainly a need for concerted action to improve governance of nanomaterials and nanotech products.54 Although this body of experts does not advocate a wholesale shift to a nano-specific regulatory regime (nor, as it happens, mandatory labelling based on particle size) it has stressed the need to focus on the functionality of ENMs. With this in mind, the Royal Commission has called for an urgent review of REACH and other relevant product and sector specific legislation in order to close potentially risky regulatory gaps.55

Conclusion

There can be little doubt that over the next few years consumers will find themselves increasingly exposed to ENMs as they go about their daily lives. Moreover, the prevailing view – at least amongst industry and governmental stakeholders – is that this generation of new technologies will prove invaluable in the battle to address the impacts of climate change, industrial pollution and water shortage. There are grounds for some concern though, for it seems that the platitudes issued by policy-makers belie a lack of firm and proactive engagement with the regulatory challenges that accompany the passage of ENMs onto the global market. The Commission’s conclusion that “current legislation covers to a large extent risks in relation to nanomaterials and that risks can be dealt with under the current legislative framework” qualified by the proviso that “however, current legislation may have to be modified in the light of new information becoming available, for example, as regards thresholds in some legislation”56 reflects a particular policy perspective on the role of law in this context: there is a clear desire to forge ahead with the Nanotech Revolution and to facilitate, so far as is possible, a smooth and rapid development of a successful European nanotech sector.

At the end of the day, it must be remembered that when the European Commission speaks of a commitment to an “integrated, safe and responsible approach” to the development of policy and law in this area,57 it does not speak solely in terms of the EU’s direct responsibilities to the consumer and the environment. After all, the Union and its institutions are creatures of ‘The Market.’ The founding principles entrenched in the treaties, in conjunction with the (massive) profit potential of this new generation of technologies, ensure that official references to “responsibility” and “safety” are firmly set against the backdrop of Member States’ combined concerns for economic “safety.” In the context of a regulatory system so firmly premised upon free market principles, it can be no other way. So far as technological risks are concerned, at least, the EU system is fundamentally flawed. This general preoccupation with markets and continual economic growth also explains why, despite regular pronouncements on the importance of wider societal debate,58 there has been no genuine attempt to engage the wider public – Europe’s citizen-consumers – in a meaningful dialogue about the benefits, risks and ethics of commercial nanotechnology. Again, of course, clear parallels can be drawn with the early years of the Biotech Revolution.

EU Member States certainly do not want to find themselves relegated to picking up the crumbs falling from the table as other, less cautious or more aggressively pro-nanotech trading partners steam ahead with carving themselves generous portion of the nanotech pie, so to speak. Hence, the proposed pragmatic approach to regulation – which emphasises the role of existing measures and relies heavily on what will, in effect, amount to governance built on reactive tweaking of risk assessment and other key pre- and post-market controls. The unpalatable truth is that in the face of extreme uncertainty, pragmatism represents the only strategy that does not challenge the very basis of the EU project. It remains to be seen whether, from the consumer perspective, this ‘safe’ free-trade-centric approach will prove adequate in the longer term: the proof, as they say, will be in the pudding.

An extremely informative nanotechnology reading list accompanies this article

Footnotes

1. Examples include: Babolat’s Drive Tennis Racket – a high performance racket manufactured using carbon nanotubes to stiffen the shaft and racket head; Tsung-Hau Technology’s 260 Den Nano Silver Far Infrared Anti-odor Healthy Socks that exploit the anti-bacterial properties of nano-silver; Ecosynthetix’s EcoSphere adhesives used in MacDonald’s packaging; beer bottles made from Imperm – a new type of plastic imbued with clay nano-particles that are as hard as glass but far stronger, so the bottles are less likely to shatter; numerous sunscreens containing nano-particulate ingredients are now widely available including Soltan Facial Sun Defence Cream, developed and marketed by Boots and Oxonica Ltd; Pilkington PLC’s Pilkington Activ self cleaning glass – apparently used to glaze the new roof of London’s St Pancras station. Examples drawn from the comprehensive inventory of nanotech products maintained by the Project on Emerging Nanotechnologies. PEN is a partnership between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and the Pew Charitable Trusts. The project’s regularly updated global database of ‘nano’ products – the Consumer Product Inventory is accessible at

2. Ibid.

3. PEN, ibid. For further details of these and other nanotech products, see PEN’s inventory, ibid.

4. PEN News, ‘New Nanotech Products Hitting the Market at the Rate of 3-4 Per Week: Nanotechnology Consumer Products Are in Your Mouth and On Your Face’, April 24th 2008, available at

5. Such figures are widely cited. See for example, the Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on the ‘Communication from the Commission: Towards a European strategy for nanotechnology’ (COM(2004) 338 final)at para 3.2.2.

6. A number of food related products are certainly available here, but so far as actual food products are concerned, the official consensus appears to be that most food applications are still at the R&D stage and there is currently no commercial use of nanotechnology in food processing in the EU. See, for example, European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), Draft Scientific Opinion: Draft Opinion of the Scientific Committee on the Potential Risks Arising from Nanoscience and Nanotechnologies on Food and Feed Safety. (Question No EFSA-Q-2007-124). Endorsed for public consultation on 14th October 2008, at p.8.

7. See, generally, Tiju, J. and Morrison, M. (2006), Nanoforum Report: Nanotechnology in Agriculture and Food, Nanoforum Consortium, April 2006, Report accessible via For details of food and food related products that are, apparently, already available on the global market, see Miller, G. and Senjen, R. (2008), Out of the Laboratory and On To Our Plates: Nanotechnology in Food and Agriculture, Friends of the Earth Europe, Australia and USA, March 2008, Appendix A, at pp.51-57.

8. Helmuth Kaiser Consultancy, Nanotechnology in Food and Food Processing Industry Worldwide, 2004, cited by Tiju, J. and Morrison, M. (2006), ibid, at p.3.

9. Commission of the European Communities, Nanotechnologies: A Preliminary Risk Analysis on the Basis of a Workshop Organised in Brussels on 1-2 March 2004 by the Health and Consumer Protection Directorate General of the European Commission, Brussels, 2004, at p.13. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/documents/ev_20040301_en.pdf

10. Ibid, at p.18. A brief and readable explanation and description of nanoparticles and fullerenes can be found in Gleiche, M., Hoffschulz H. and Lenhert, S., Nanoforum Report: Nanotechnology in Consumer Products, Nanoforum Consortium October 2006, at pp.4-7. Report accessible via www.nanoforum.org

11. European Commission Communication, Towards a European Strategy for Nanotechnology. COM (2004) 338 final, at p.4.

12. European Commission Communication, Regulatory Aspects of Nanomaterials, COM (2008) 366 final, at p.3.

13. Although there are also concerns about the longer term risks associated with manufactured nanomaterials incorporated into products, it is this class of nanomaterials that is considered to present the most immediate toxicological hazard to both man and the natural environment. See, for example, Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, Novel Materials in the Environment: The Case of Nanotechnology. (London, Stationary Office, November 2008). See, in particular, Chapter 3 and paras 4.48-450 at pp.64-65.

14. European Commission Communication, Nanosciences and Nanotechnologies: An Action Plan for Europe 2005-2009. First Implementation Report 2005-2007. COM (2007) 505 final, at p.8.

15. Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (2008), note 13 above.

16. Ibid, at p.30.

17. See EC Treaty, Article 95, which imposes a base line obligation to provide consumers with a “high level of protection” in the context of market harmonisation measures. This commitment is also found elsewhere in the Treaty (e.g. Article 153) and is regularly reiterated by the European Commission and other key EU institutions. In the context of nanotechnologies, see, for example, European Commission Communication, Nanosciences and Nanotechnologies: an Action Plan for Europe 2005-2009. COM (2005) 243 final, at p.10.

18. This reassuring term has been bandied around by all key policy makers since nanotechnology began to attract their attention. See, for example, the European Commission’s first major ‘strategy’ document: European Commission Communication, Towards a European Strategy for Nanotechnology. COM (2004) 338 final, at p.18.

19. It is interesting to note that the first moves toward establishing a meaningful role for consumer policy at supra-national level were made back in the 1970s. See, for example, Council Resolution of 14 April 1975 on a preliminary programme of the European Economic Community for a consumer protection and information policy ([1975] O.J. C 92/1) – the first in a series of Resolutions adopted by the Council. However, it was not until the Maastricht Treaty’s insertion of Article 129(a) into the EC Treaty in the early 1990s that any really significant progress was made. The provisions set out in what was Article 129(a) have since been reinforced via the Amsterdam Treaty which characterised the consumer as an equal stakeholder in the marketplace – see now EC Treaty, Article 153. On the evolution of Community consumer policy generally, see Weatherill, S. (2005), EU Consumer Law and Policy (Cheltenham, Edward Elgar).

20. As Stephen Weatherill explains, the assumption was that, “..the consumer [would] benefit from the process of integration through the enjoyment of a more efficient market, which [would] yield more competition, allowing wider choice, lower prices and higher quality products and services. The substantive provisions of the Treaty, such as those designed to remove barriers to the free circulation of goods, persons and services….are designed indirectly to improve the lot of the consumer.” Weatherill, S. (1997), EC Consumer Law and Policy (London, Longman), at p.5.

21. One of the implications of this is that there can be a tendency for the underlying free trade imperative driving the harmonisation process to drive consumer protection standards down to the lowest common denominator rather than up to the highest. This point has been noted by various commentators. See, for example, MacMaoláin, C., EU Food Law: Protecting Consumers and Health in a Common Market (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2007), at p.1. For further discussion regarding market harmonisation legislation and its consumer protection value also see, Weatherill, S. (2005), note 19 above.

22. i.e. unfamiliar, man-made risks characterised by novelty and uncertainty that cannot be easily quantified and are, thus, not amenable to conventional risk analysis processes – and, in particular, economic and science-driven risk assessment – in the way that more familiar, traditional risks will be.

23. See, e.g. Article 14(2) of the EC Treaty which explains the nature of the internal market that and underpins, and defines, the European project: “The internal market shall comprise an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured in accordance with the provisions of this Treaty.”

24. Although, as history shows, even here there are no guarantees. See, for example, Wargo, J. (1998), Our Children’s Toxic Legacy: How Science and Law Fail to Protect Us from Pesticides. (Yale University Press); Carson, R. (1962), Silent Spring. (originally published in the USA by Houghton Mifflin. Most recently reprinted in the UK by Penguin Books in 1999); Pennington, H., When Food Kills: BSE, E. Coli and Disaster Science (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2003).

25 See, for example, Consumers’ Association (2007) Which? Report on the Citizens’ Panel examining nanotechnologies, prepared by Opinion Leader, at p.9; Editorial (2007) ‘A Little Knowledge’, Nature Nanotechnology, Vol.2, No.12, p.731; Editorial (2009) ‘Getting to Know the Public’, Nature Nanotechnology, Vol. 4, No 2, p.71. On public perceptions of nanotechnologies more generally, see the following articles and letters also published in this 2009 edition of Nature Nanotechnology: Currall, S. (2009), ‘Nanotechnology and Society: New Insights into Public Perceptions’, pp.79-80; Kahan, D., et al., ‘Cultural Cognition of the Risks and Benefits on Nanotechnology, pp.87-90; Scheufele, D., et al., ‘Religious Beliefs and Public Attitudes Toward Nanotechnology in Europe and the United States, pp.91-94.

26. The European Union Online, the official website of the European Union, http://europa.eu/

27. European Commission (2005), note 17 above, at p.2.

28. Note the various documents on the resource list.

29. COM (2008) 424 final.

30. See, European Commission (2008), ibid. The provision that is particularly reassuring in its tone is para.4.2. on p.8: “Given the deficit of knowledge of the environmental and health impacts of nano-objects, Member States should apply the precautionary principle in order to protect not only researchers, who will be the first to be in contact with nano-objects, but also professionals, consumers, citizens and the environment in the course of N&N research activities.” Other references to ‘precaution’ and to the ‘precautionary principle’ can be found at recital (2), p.2; para.3.3 at p.6; para.4. at p.7; para. 4.2.4. at p.10.

31. European Commission, Communication on the Precautionary Principle. COM (2000) 1 final. It should be noted that despite the fact that Article 174 of the EC Treaty refers only to Community policy on the environment, the Commission acknowledged the broader relevance of the precautionary principle: “Whether or not to invoke the Precautionary Principle is a decision exercised where scientific information is insufficient, inconclusive, or uncertain and where there are indications that the possible effects on the environment, or human, animal or plant health may be potentially dangerous and inconsistent with the chosen level of protection.” COM (2000) 1 final, at p.7.

32. See the text of Article 174 of the EC Treaty. Note in particular, the text of the 3rd paragraph which expressly states that the Community “shall take account of: available scientific data; environmental conditions in the various regions of the Community; the potential costs and benefits of action or lack of action; the economic and social development of the Community as a whole and the balanced development of its regions.”

33. The Wingspread Declaration on the Precautionary Principle was adopted in 1998 at a Conference organised by the Science and Environmental Health Network that brought together thirty five academic scientists, grass roots environmentalists, government researchers and labour representatives from the USA, Canada and Europe to consider how the precautionary principle could be formalised and brought to the forefront of environmental and public health decision making. See Raffensperger, C. And Tickner, J (eds) (1999), Protecting Public Health and the Environment: Implementing the Precautionary Principle. (Washington, Island Press).

34. COM (2008) 366 final.

35. Ibid, at p.8

36. See, for example, Miller, G. and Senjen, R. (2008), Out of the Laboratory and On To Our Plates: Nanotechnology in Food and Agriculture, Friends of the Earth Europe, Australia and USA, March 2008, in particular at p.2. and pp.37-43.

37. COM (2008) 366 final.

38. Ibid, at p.3.

39. Ibid, at p.8. Whether or not one accepts official assertions that existing legislation is capable, in principle at least, of dealing with risks associated with engineered nanomaterials, it has to be agreed that the current lack of a solid (scientific) knowledge base against which to measure the efficacy of existing controls, or upon which to base new, targeted measures, is a major problem. This barrier to effective risk management is exacerbated not only by the globalised nature of modern supply chains – which ensures that the ripple effects of any risks that do materialise are likely to be extensive – but also by the ability of major industry players to influence political and research agendas, use law to their advantage and to disregard public opinion and suppress research findings not to their liking. Much has been written on such matters. See for example, Monbiot, G. (2000), Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain. (London, Macmillan); Bakan, J. (2004), The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power. (London, Constable and Robinson Ltd); Donson, F. (2000), Legal Intimidation. (London, Free Association Books); Shiva, V. (2000), Stolen Harvest: The Hijacking of the Global Food Supply. (London, Zed Books); Korten, D. (2001), When Corporations Rule the World, 2nd Edition. (Connecticut, Kumarian Press Ltd); for a discussion of how human rights arguments are used by corporate actors as well as consumers see Harding, C., Kohl, U. and Salmon N. (2008), Human Rights in the Market Place: The Exploitation of Rights Protection by Economic Actors. (Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing Ltd).

40. Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 concerning the registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction of chemicals, establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC. [2006] O.J. L396/ 1.

41. Ibid, Article 1(3).

42. Ibid.

43. Ibid, Article 3(1).

44. Note, for example, the text of the draft Novel Foods Regulation: Regulation on novel foods and amending Regulation (EC) No XXX/XXXX [common procedure]. COM (2007) 872 final. For overview of EU policy on novel foods and the ongoing regulatory review, see the European Commission’s website at: For a discussion and analysis of this specific proposal and its application to novel ‘nanofoods’, see Salmon, N. (2009) ‘What’s Cooking? From GM Food to Nanofood: Regulating Risk and Trade in Europe’, Environmental Law Review, forthcoming.

45. Where these larger quantities are at issue, the registrant is obliged to submit a detailed report evidencing compliance with the over-arching requirement that such products must not present a danger to .human or environmental health.

46 Noted by the Commission (2008), op cit, note 5, at p.4.

47 Ibid.

48. evidenced, for example, by the contamination of the environment and the food chain with various persistent chemicals. On such matters, see for example, Wargo (1998) and Carson, R. (1962), note 24 above. On n the issue of GMOs and contamination of the environment and the food chain see, for example, Partridge, M. & Murphy D.J., (2004) ‘Detection of genetically modified soya in a range of organic and health food products: Implications for the accurate labelling of foodstuffs derived from potential GM crops’ British Food Journal, 106, 166–180; Orson (2002) ‘Gene Stacking in Herbicide Tolerant Oilseed Rape: Lesson From the North American Experience’, English Nature Research Reports, No.443; Quist, D. & Chapela I. H. (2001), “Transgenic DNA Introgressed into traditional landraces in Oaxaca, Mexico.” Nature, 414, pp.541-542; Metz & Futterer (2002) ‘Suspect Evidence of Genetic Contamination’, Nature, 416, pp.600-601; Quist, D. & Chapela I. H. (2002), “Reply to Letters.” Nature, 416, p.602.; Dale et al (2002) Potential for Environmental Impact of Transgenic Crops’ Nature Biotechnology, 20, pp.567-574; Macilwain, C. (2005) ‘US launches probe into sales of unapproved transgenic corn’. Nature, Vol. 434, p. 423; Salmon, The European Laboratory: The Construction of Consumer Rights in Europe’, in Harding, C., Kohl, U. and Salmon N. (2008), note 39 above, where a brief discussion of GM contamination from the European perspective can be found at pp.125-132. Note also, the online GM Contamination Register maintained by Greenpeace and GeneWatch UK, accessible at http://www.gmcontaminationregister.org/

49. See REACH, Article 129.

50. As per Article 174 of the EC Treaty and supported / clarified by the European Commission’s Communication on the Precautionary Principle. COM (2000) 1 final.

51. In the context of REACH see recital (69) of the Regulation.

52. See references at note 48 above.

53. Bearing in mind the reality of the ‘nano’, such an approach would be problematic in terms of enforcement in any case. After all, aside from the obvious issue of (in)visibility, other factors such as whether or not particles are ‘free’ or ‘bound’ as well as variability in particle size and agglomeration can make it difficult to determine with any consistency and reliability, the actual size of particles in commercial applications. The Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution suggests that it may be more sensible to base any labelling requirements on the properties and functionality of specific nanomaterials. See, e.g., the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (2008), note 13 above, at p.69.

54. Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution (2008), ibid, note 7.

55. Ibid, at p.78, para 5.10. See Chapter 4 of the report for detailed coverage of the regulatory challenges.

56. European Commission (2008) op cit, note 12 at p.3.

57. See, for example, ibid, at p.3.

58. Official reassurances that public understanding and acceptance of commercial nanotechnologies is essential litter the publications coming out of institutions such as the European Commission. The following from the European Commission is fairly typical in its tone: “Societal acceptance is a key aspect of the development of nanotechnologies. The Commission’s role as a policy making body is to take account of people’s expectations and concerns. Not only should nanotechnologies be safely applied and produce results in the shape of useful products and services, but there should also be public consensus on their overall impact. Their expected benefits, as well as potential risks and any required measures, must be fully and accurately presented and public debate must be encouraged, to help people form an independent view.” European Commission COM(2007) 505 final, note 14 above, at pp.7-8. However, despite the reassuring rhetoric of such pronouncements, the reality on the ground is that the starting point is inevitably that innovative nanotech applications are desirable and that any wider societal debate should be directed at promoting public acceptance of this latest technological revolution. For broad coverage of the social and ethical issues associated with nanotechnologies, see, Sandler, R. (2009), Nanotechnology: The Social and Ethical Issues, Project on Emerging Technologies (PEN), (Washington, Woodrow Wilson Centre). Report available via http://www.nanotechproject.org/

If this article was useful to you please consider sharing it with your networks.